Broke Jail

by D. H. Johnson

I.

The directors of the Dan and Beersheba Railway Company, you remember, treated themselves and their friends, last summer, to an excursion over so much of their road as was then in running order. Of course a good many newspaper men were taken along as historiographers of the trip. When I remember all the able and fervent articles, celebrating the present and prospective glories of the Dan and Beersheba Railway and its imperial land-grant, that were inspired by that free ride, I cannot but think that the excursion, great success as it was in all respects, was greatest in the way of inexpensive advertising. You remember that the more enterprising excursionists, including, of course, the newspaper men, took a construction train and went far beyond the then stopping-place for passenger-cars, to witness the operations of a new steam track-laying machine.

The machine was superintended by the patentee, a stout gentleman of about forty-five, dressed in a cool business suit of pearl gray. His clean-shaved face was somewhat brown and knobby, and was an unmistakably Hibernian face of the good-humored variety. Its most noticeable peculiarity was that the lips seemed to be pushed a little forward by the front teeth.

I stood near him as he politely and with rare perspicuity explained the principles and modus operandi of the machine. His eyes rested upon me and mine upon him as he talked. Mutual recognition dawned and grew brighter in our minds and eyes, until he abruptly closed his explanation and walked away. As he went, he cast back at me a look and nod of his head which plainly meant, “Say nothing, and follow me.” I followed until we had gone out of ear-shot of the others. He then turned to me and said, —

“You know me, don’t you?”

“Yes; you are Mick Mullen.”

“You haven’t come here to do me an ill turn, I hope.”

“Certainly not.”

“Then for God’s sake don’t say Mick Mullen again! Let Mick Mullen and all his works rest; you know what I was and you see what I am. If a whisper of what you know should get abroad here, I’d just put a pistol to my ear and blow my brains out.”

“My dear fellow, you have nothing to fear from me. You ought to have taken that for granted.”

“Sure, I ought. But isn’t it provoking? Only two days ago I shaved off my beard, and here I am twigged already.”

“Does your beard disguise you so effectually?”

“Black hair and whiskers and mustaches work wonders on a sandy complexion, especially if a fellow has a mouth full of big front teeth. When I have my beard flowing free and black as a raven’s wing, the devil himself wouldn’t know me, intimate as he was with Mick Mullen the time we know of. I’ll get leave of absence to-morrow, and go into the hills and stay there till my beard is long enough to dye.

“Call me Jonathan Elder,” continued he with great earnestness, “while you’re here and after you’re gone. Think of me by that name. It is a matter of life and death to me that Mick Mullen should not come to light.”

After some further talk we rejoined the crowd around the machine, where my friend resumed his explanations, and where I called him Mr. Elder, as often as a suitable opportunity occurred, except once, when, as if by a slip of the tongue, I addressed him as Jonathan.

Having mastered the mystery of laying railway track by steam, our party returned as we came. Ames, of the Dusenbury Express, said to me as we smoked our cigars on a dumping-car, —

“That engineist, or machineer, or whatever he is, seems to be an old acquaintance of yours.”

“Yes,” said I, “he is an uncommonly ingenious fellow. He once did a very nice job for me. It seems he has had his name changed since I knew him. He was on nettles to-day for fear I should call him by his old name and put him in for an awkward explanation. So he took me aside to introduce himself to me as Jonathan Elder, Esq.”

What I told Ames was literally true. Yet in spirit and substance it was a lie, a well-constructed, artistic lie, I hope; such a lie, I flatter myself, as no mere tyro can tell.

I propose to be more candid and explicit with the reader than I was with Ames, in telling the story of my first acquaintance with Mick Mullen, otherwise Jonathan Elder, Esq. And yet I shall take such liberties with literal facts of the case as shall seem to me to be necessary, to prevent mischievous discoveries.

II.

Locofocoville, February 19, 1851.

Dear Nephew, — Your mother informed me, last summer, when she was here, that you were a printer, and sometimes wrote for the papers. She showed me some of your literary performances, which were not so bad as I dreaded and expected when she went to her trunk for them.

I want you to come and start a whig paper at Locofocoville. I am told that you will need from twelve to fifteen hundred dollars, to purchase the necessary outfit. I do not propose to give you a dollar. But I will subscribe and pay in advance for one thousand copies of your paper for one year, upon the following conditions: —

First, you must send the full number of my papers, as I shall from time to time direct, without discount or defalcation, They will all be sent to democrats, who would not probably patronize you of their own accord. No matter how many are refused and sent back, I shall keep my list full. Occasionally some man whose name is on my list will subscribe and pay for the paper himself. I must be promptly informed of such cases, so that I can at once substitute another name on my list.

Second, you must make no personal attacks, and you must reply to none made upon you. You must confound and bewilder your adversaries by publishing a gentlemanly political newspaper.

Third, you must never make mention of gentlemanly and efficient hotel clerks, massive and brilliant railroad conductors, beautiful and accomplished steamboat captains, and the like. The dead-head literature of this age is more servile and nauseating than the old time dedications to patrons.

Fourth, after election you must not print “Now that the smoke of the late political conflict begins to lift from the battle-field of the contending tickets, and corrected lists of the killed, wounded, and missing are beginning to come in,” etc., — or words to that effect, — oftener than once in two years.

Fifth, you must condense the news, each week, into a single article, to be written, not clipped; and you must honestly give credit not only for what you copy, but for what you condense, from other papers.

Sixth, your paper must be of fair size and well printed, and must be called The Locofocoville Whig. Terms, two dollars a year.

If the above proposition and conditions suit you, let me hear from you without delay. Your aunt,

Eunice Henderson.

To Mr. Thomas Wynans,

Harrisburg, Pa.

III.

The above letter soon produced the first number of the Locofocoville Whig. From that time to this, only two Saturdays have passed without the appearance of a number of that paper. The non-appearance of the Whig on these two Saturdays is what I have set out to explain.

My aunt was a tall, bright-eyed, broad-shouldered lady of forty-five or there-abouts. She was a hearty hater of meanness, and a merciless contemner of shams and quacks. She was bountiful to the poor, especially the disreputable poor, against whom all other hands were closed. Her position as a lady of wealth and influence enabled her to indulge in some eccentricities and disregard some conventionalities. Wherever she went with her long, rapid, elastic steps, she caried with her a breezy atmosphere of good sense and good feeling. She was the most magnetic person I ever saw. It was impossible to be in her company without being influenced by her strong, healthy, and slightly whimsical nature. She was an insatiable reader of the English classics, and of such modern English literature as is destined to become classic. Locofocoville was intensely democratic, and my aunt was the stanchest of whigs. Nevertheless she was so popular there as to be regarded in the light of a cherished institution rather than a favored individual. She was a childless widow, and was by far the richest person in the neighborhood.

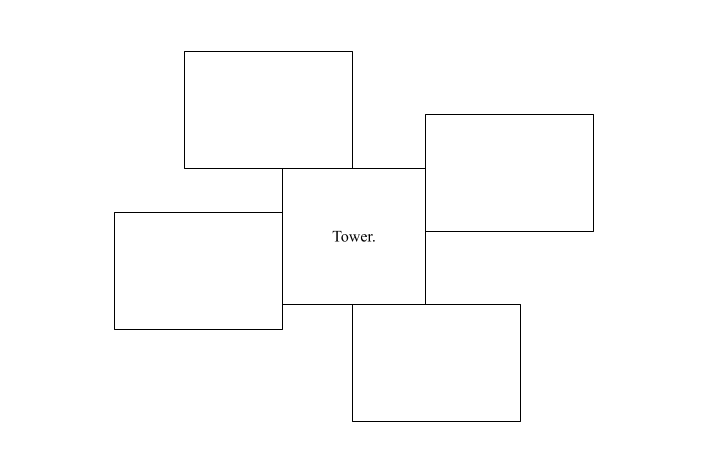

She lived in a curious, rambling house, or collection of houses, built by her to take the place of a former residence which had been burned down. This villa was built of stone and roofed with sheet iron, and was as nearly fire-proof as the building facilities of Locofocoville would permit. The main buildings, four in number, were two stories high, and arranged about a three-story tower, thus:

The main entrance was through the tower. In the centre of the tower was a grand circular stairway. All the rooms were spacious and lofty, those in the second stories of the main buildings and that in the third story of the tower being vaulted. This mansion stood, and still stands, about a mile from the village, in the middle of a larger farm.

“My dear Tom,” said my aunt, “I can endure as much of my own society as most people; but I do sometimes get a little lonely. You must come and stay with me. It will be a deed of charity. There is a fair library here, and you can have your choice of half a dozen rooms.”

I selected the third story of the tower, partly because it commanded a find prospect in every direction, and partly because I thought I should be less liable to be disturbed there than elsewhere. In the latter particular I was disappointed. The tower communicated, either immediately or by means of a short passage, with every room in the house; it being a cardinal principle in my aunt’s theory of house-building that one should never be compelled to pass through one apartment to reach another. This arrangement, aided by the grand stairway in the middle of the tower, made my room a gathering-place for all the noise in the house. One who has never occupied a room so situated cannot readily imagine what a perfect whispering gallery it is. I remained true to my first choice, however, partly because I did not like to lose any of the prospects commanded by my windows, but mainly because I did not like to confess that I had made a foolish selection; still less, that I had been an involuntary listener to nearly every word that had been spoken in the house while I was in my room.

Independently of my aunt’s liberal patronage, my paper succeeded far better than I had anticipated. The village already had a democratic paper. This organ of public sentiment complimented the typographical get-up of my first issue, but deplored its politics; wished the new-comer success, but could not venture to predict as much. After that my neighbor pitched into me in the approved swash-buckler style of newspaper controversy in those days. Having learned that my paper was largely patronized by Mrs. Henderson, he was never tired of calling me the nephew of my aunt. I drew the sting of this nickname, I find on reference to my filed, by the following somewhat turgid paragraph: —

“The Herald” (that was the name of the rival print) “having learned that this paper is much indebted to the liberality of Mrs. Henderson, and that we are related to that lady, took occasion in a recent issue to call us ‘the worthy nephew of his aunt.’ We esteem this a high compliment and a neat witticism. We are grateful to our neighbor both for his civility and for his wit, qualities rare enough to deserve favorable mention whenever they appear.”

Further than that, I took notice of no attacks that were made upon my paper, but pursued the journalistic path marked out by my aunt’s letter. The Herald and other democratic newspapers there-about soon tired of berating a paper which could not be provoked into an unfriendly utterance, even by way of retort. The editor of the Herald was a good fellow. He and I soon became warm friends. Many of the persons whom my aunt caused copies of my paper to be sent became subscribers on their own account. As long as she lived my aunt kept her list full, and she took measures, as will presently be seen, to have a similar list kept full after her death so long as I should be a newspaper publisher. This continued gratuitous distribution of a thousand extra copies of the Whig, while it added appreciably to my paper bills and press-work, proved an unequaled advertisement. Since my aunt’s death I have continued to sow broadcast a thousand extra copies of my paper every week, for a reason which will soon appear, and have reaped a satisfactory harvest of patronage. My advertising business has been quite as much enlarged in this way as my sales of papers. My systematic abstinence from newspaper warfare has probably caused a small class of readers to reject the Whig as an insipid affair. But it has met the approbation of a larger and better class, to whom a country publisher must look for his permanent supporters. In short, I have good reason to be satisfied with my own mode of publishing a rural newspaper, and I take this occasion to acknowledge that I probably should have come far short of striking out so successful a line of tactics for myself if left to my own devices. I am quite clear that my aunt’s good advice was of more value to me, as a publisher, than her great liberality.

IV.

One evening late in July, the second summer following the establishment of my printing-office, I carried up to my room in my aunt’s house a big bundle of exchanges, and went to work upon my weekly news article.

I was and am still in the habit of bestowing much labor upon that article. I try not only to collage a complete synopsis of current events, but to weave into it such original reflections, grave and gay, as are worthy to be printed. It requires more tact and judgement, and far more labor, than ordinary readers would suppose, to prepare such an article. The several items of news as they come to hand have to be epitomized on separate slips of paper, and a sort of reportorial perspective has to be observed, by which events are given prominence and space in proportion to their importance. Doings otherwise equally momentous or frivolous are, for the editor’s purpose, important in the inverse ratio of their distance from the office of publication. After the news article is in type and “made up,” items of intelligence that come to hand have to be thrown into a chaotic postscript. Gentlemen who have from time to tome filled my editorial chair in my absence have found this same news article their greatest difficulty. I worked at my task until after midnight without interruption. True, I heard the nightly discourse between James and Maggie Penfield, my aunt’s right-hand man and woman, when they retired to their room over the dining-hall, and I heard the two servant girls exchange confidences and compare notes as they lingered in the passage which led to their dormitories; but these eavesdroppings of the household gossip had long since ceased to annoy or hinder me.

About half an hour after midnight I heard a faint, scraping noise somewhere down-stairs. At first I paid no attention to it. Just as I began to wonder what it could mean, it ceased altogether.

I had now finished my night’s labor and was busy revising and arranging my manuscript. While puzzling intently over an involved and stilted paragraph, and trying to reform it by erasures and interlineations, I was startled by unmistakable sounds of stealthy, muffled footsteps below. My first thought was of robbers. Pshaw! said I to myself, it is only aunt or one of the servants out of bed and walking barefoot. Having settled down in this belief, I resumed my labor and continued it perhaps five minutes, occasionally hearing but giving no heed to soft footfalls.

Suddenly came my aunt’s voice, “Who’s there, and what do you want?” Then followed a confused sound of many muffled footsteps, a pistol-shot, a groan, and a heavy fall. I seized my revolver and precipitated myself down-stairs, I know not how.

The front-door of the tower was open and the moon was shining in. My aunt in her white night-clothes was lying on the floor near the foot of the stairs. Three men were running down the pathway leading to the high-road, one of them considerably behind the others. I fired all of the barrels of my revolver after the retreating figures. The hindmost man stumbled at the second shot, but instantly regained his feet and fled faster than before.

I went to my aunt, lifted her from the floor, carried her to her room, and laid her on her bed. It seemed to me that she gasped for breath while I was carrying her. Probably I was mistaken, for it afterwards appeared that she had been shot through the heart.

It was not until I had lighted a candle that Maggie Penfield, the biggest and bravest of the servants, made her appearance.

“Maggie,” said I, “call your husband and the girls. Your mistress is murdered!”

Maggie seemed stupefied. I repeated my order again and again before she appeared to comprehend it. At last she lighted a lamp, took my candle, and went and called the other servants, who had all been awakened by the first pistol-shot, but had remained quaking in their beds.

I explained to them what had happened as well as I could, and told them to run to the village and call the doctor, the sheriff, and the magistrate. Nobody stirred.

“If you are afraid to go,” I said, “stay here, and I will go.”

“Indeed, sir, they are afraid to go or stay, I do be thinking; and small blame to them,” said Maggie. I’ll go, sir, and you can trust them to folly me.”

Suiting her actions to her words, the brawny Irishwoman started off at a great pace, closely followed by the other servants. I did not realize, until I saw them pass into the moonlight, how scared and wild they all appeared; nor did it occur to me until many days afterwards that the whole party wore shoes without stockings, that the women were clad in their scanty summer night-gear, or that James had progressed with his toilet only so far as to slip into his pantaloons and fasten one suspender.

When they were gone, I took the lamp and examined the premises for traces of the murderers. The front-door had been opened by means of a pair of nippers inserted into the key-hole, so as to seize and turn the key, which was in the lock. Upon examining the key, I found the end of it worn quite bright. Evidently the nippers had slipped many times, and that was probably the cause of the scraping noise I had heard. There was a sort of vault under the stairs on the first floor of the tower. It appeared like an ordinary closet, but was lined with iron, and had an iron door painted to resemble wood. There my aunt kept her valuables in an old-fashioned strong-box, fastened with a padlock, which could have been carried off bodily by two strong men. The murderers had opened the vault, probably with a skeleton key, and it had doubtless been their intention to rifle or carry off the strong-box. My aunt, whose courage amounted to positive contempt of danger, had come among them in time to prevent them from meddling with it. I thought it more than likely that she had seize one of them, intending to hold him until she could summon help, and had thus met her death.

After examining the interior of the house pretty thoroughly, I went outside to look for tracks, but found none. I then remembered that all the footsteps I had heard had been muffled, as though made by one walking without shoes. I concluded that the murderers had worn moccasins, — then somewhat in vogue in that part of the country. They would make no impression on the firm turf and hard, graveled walks around the house.

Having made these observations, I returned to the room where my aunt’s body was laying.

I set the lamp on the mantel, where it shone full upon the dead face. The expression was stern, but not pained nor angry. I leaned against the mantel and watched those rigid features, I know not how long. It seemed to me that my messengers would never return. My thoughts would not stay fixed upon any subject. While speculating as to the probability of my having wounded one of the flying murderers, I wandered off into a series of crude reflections upon the imperfections of my revolver, an old-fashioned bundle of small, short barrels turning around a common centre, and forming a fire-arm of little range and less accuracy. The boys used to call such weapons Allen’s pepper-boxes, if I remember rightly. My mind went along this irrelevant track, until I fancied I had invented a better repeating pistol. I was going on to apply the principle of my invention to rifles, muskets, and cannons, when I became suddenly conscious of the impertinence of such a train of thought at such a time. I then began to think of the sterling qualities of the deceased, and her great kindness to me. My thoughts ran back and forth along the line of her history, but soon stole away into idle conjectures concerning an old gray horse which had long been a pensioner in her pastures and stables. I struggled to construct some theory which should account for his being named Black Prince, he being, as I have said, a gray horse. I was about surrendering my judgement to the feeble surmise that he had originally been black and had turned gray from old age, when I was startled by what seemed to be a change in the expression of the dead face. My aunt seemed to be smiling grimly, as she had been wont to smile when she heard or read a foolish thing.

Of course I understood instantly that the appearance was due to the flickering of the lamp, caused by a light breeze, just then springing up. I set the lamp out of the draught, and doing so threw the light on the profile of the dead face. This seemed to give it the expression which it had generally worn during the sermons of our excellent, prosy minister, an expression of mingled weariness and resignation highly edifying.

This new fancy was leading me into a maze of nonsense concerning sermons, when I heard the voices of approaching people. They soon arrived, — the servants, a physician, a magistrate, the sheriff, the minister, three or four other gentlemen, and two ladies. I told them my story with much great difficulty. I had not been conscious of grief, but now I felt an ache in my throat which rendered me almost speechless. I could only give the merest outline of what had happened, before I broke down and wept like an infant. My grief was contagious. The house was filled with the lamentations of the women, and the men were visibly affected. At last Maggie Penfield took me by the arm and led me to my room. I sobbed myself to sleep, and did not wake until ten o’clock or later.

When I came down-stairs I found that a coroner’s inquest had been organized, and that the servants had already been examined. Of course I was called upon to state under oath what I knew of my aunt’s death. I did so as clearly and succinctly as possible. The doctor then examined the wound, and testified that the deceased had been shot through the heart, the appearance of the wound indicating that the murderer had been sitting or lying on the ground when he fired. The verdict of the coroner’s jury was to the effect that the deceased had come to her death by a gun-shot wound at the hands of some person unknown.

It was now Saturday, my publication day. The editor of the Herald behaved very handsomely. He went to my office and helped the foreman prepare the “inside” of the paper for the press, himself furnishing a well-written account of the murder and a generous tribute to the memory of the deceased.

The funeral took place on Monday. I went from the grave to my office, and resumed my editorial labors. On the Thursday following, the papers of the deceased were examined in the presence of such of her relatives and those of her deceased husband as chose to be present. Her lawyer readily found a will which he had drawn only a few weeks before. My aunt’s husband had left all his property to her. In her will she had scrupulously given all that had belonged to him to his brothers and sisters in common. A considerable portion of her estate, however, had belonged to her in her own right before her marriage. This she divided among her own relatives. I was liberally provided for. The homestead farm and the library were left to me, and I was named in the will as the sole executor and residuary legatee. There was a passage in the will enjoining it upon me to continue the publication of the Locofocoville Whig newspaper at least ten years after her death, if I should so long survive, and while I should publish the paper to distribute weekly one thousand copies of it to non-subscribers; it being left to my honor to fulfill her wishes in these respects.

V.

The sheriff and his deputies and not a few volunteers were very busy during the five days succeeding my aunt’s death, trying to find her murderer and his companions, or some clew whereby to trace them; but all in vain. This signal want of success on the part of the officers probably set somebody to thinking — I never knew who started the idea — that they were on the wrong trail. The day after the reading of the will, as I went to my office, I met two or three people with whom I was acquainted. They answered my morning salutations hurriedly and constrainedly, and got out of my way as quickly as possible. I paid little attention to these things at the time, as I was very much preoccupied, but I soon had occasion to recall them. When I arrived at the office, every one there looked at me in a strange way, but none of them spoke to e as I passed to an inner room where I had set up my sanctum. They acted, so it seemed to me, as people do when surprised by the sudden appearance of a person about whom they have been talking. As soon as I had closed my door a buzz of earnest whispering sprung up in the outer room, which I could hear, but no word of which I could distinguish.

There was then in the office an old tramping “jour,” an Englishman and a thorough-going vagabond. It was then a rule among printers that a journey-man on his travels, and out of money, had to be furnished with employment at whatever office he applied for it long enough to enable him to earn the means of continuing his rambles, even if a regular “hand” had to surrender his “case” temporarily to make room for him. Taking advantage of this regulation, old George Armstrong had tramped wherever the English language was put in type. He affected a seedy, moldy style of gentility. He had an eccentric habit of purchasing a quart of whisky once in two or three weeks, retiring from the busy haunts of men, and lying drunk as long as the liquor lasted. This habit he justified upon the ground that it was expensive and ungentlemanly to drink at the bars of public-houses. This demoralized disciple of Faust came to me in my room, and desired to settle, saying that he intended to resume his travels at once.

“I thought you meant to stay with us a few days longer, Mr. Armstrong,” said I. “We have so much job-work on hand that you will leave us short-handed if you go now.”

“I had intended to work here a few days longer,” said he, “but the fact is, sir, I don’t think the office can go on much longer.”

“The office can’t go on much longer! What ails the office?”

“If you don’t know it sir, you ought to be told. You are suspected of the murder of your aunt. A great excitement is getting abroad in the street. You are in danger of violence every moment. If I might venture to advise, sir, I should say you ought to take prompt measures for your own safety. I need not say, sir, that I have traveled too far and have seen too many men to doubt your innocence; but I do assure you, sir, the people are greatly excited. The popular fury is spreading from fool to fool like a prairie fire in a high wind. Oh, sir, I have reason to know what a hopeless thing it is to face the blind fury of a mob! No wise man will risk it. I am too old and worthless to be of any use to you in this emergency. Please pay me my little wages and let me go.”

I paid the old fellow what he claimed, and he was gone before I had fairly realized the full import of his words. When he was gone and I had time to reflect, all the strange conduct I had witnessed that morning came back to me with awful significance.

I wrote a brief note to the sheriff, saying that I had just heard that I was suspected of the murder of my aunt, and requesting him to come and take me into custody at once. This note I committed to my printer’s devil, an inky little Arab, true as steel and cunning as a ten-year-old fox. (He is now the publisher of an orthodox religious newspaper.)

I watched my messenger from my window. He comprehended the situation better than I did. Instead of going into the street with my note in his hand, he hid it in his hideous paper cap, took a water-pail in one hand and a big brush, used for cleansing type, in the other, and sauntered out, whistling a negro melody, until he had got beyond the crowd which had already gathered in formidable numbers in front of the office. Then he dropped his impedimenta and ran like a hunted squirrel.

The sheriff soon came with a posse of about twenty men. They placed me in their midst and marched away with me at once. The sheriff explained to me that any attempt to have an examination before a magistrate would be dangerous; that my only safety lay in being lodged without delay in jail. It was about a quarter of a mile from my office to the jail. The crowd around us became more numerous and demonstrative, every step. But the sheriff and his posse were resolute men, besides being leading citizens, and were ostentatiously well armed. No actual violence was offered, though many threats were made by the howling crowd. The sheriff did not content himself with locking me in the jail. He put me in the single felon’s cell, which was fortunately vacant at that time. I was not ironed. A chair, a mattress and blankets, a small stand, and writing materials were furnished to me, and I was made as comfortable as circumstances would permit.

Fortunately for me, none of the sheriff’s officers believed in my guilt. There was therefore no danger of collusion with the mob. The sheriff and his men believed in my innocence, probably, as much because of their unwillingness to admit to themselves that they had been on the wrong track thus far, and had missed the true theory of the case altogether, as for any other reason. When a man’s good opinion of his own sagacity is enlisted in your favor, you can depend upon him.

The sheriff himself had been a soldier in the earlier part of his career. He was a big, burly, good-natured, bald-headed fellow, and immensely popular. I could not have named another man under whose protection I should have felt as safe as I did under his.

From the time that I was locked up until late that night, a numerous and noisy crowd hung around, keeping one another up to the highest pitch of excitement and continually threatening to tear down the old jail to get at me. They were led by one Stanley, a bully and a ruffian of the lowest type. There was a little grated window in the felon’s cell, about five feet from the floor, but fully nine feet from the ground outside. About midnight, Stanley and several others approached this window. Stanley placed a light ladder against the wall and was proceeding to mount it, with a pistol in his hand, when Charlie (that was what everybody called the sheriff) suddenly appeared to him, knocked his ladder down, and seizing him roughly by the collar whispered something in his ear. The ruffian slunk back, cursing terribly but still retreating. His curses were all directed at me, not one of them at Charlie.

“Boys,” said the sheriff in his deep, good-humored tones, “go home, every man and mother’s son of you, or I’ll put you all in the bull pen, if I have to build a new one to hold you. Stanley, if you meddle with this building again, I’ll send you off, a quarter of a pound at a time. Come, boys, you know I’m boss here. Clear out! I an’t a-going to set up all night to watch your damn nonsense. Clear out! Clear out!”

“Nobody blames you, Charlie. You’re doing your duty,” said a voice in the crowd, and the mob gradually drew off. When they were gone, the sheriff came to the cell and brought me what he called a “hoss” pistol and a good supply of ammunition.

“I’m going to bed,” said he. “I’ve be[e]n up most of three nights runnin’. If nothing happens, shan’t get up till to-wards fall. If any son of a gun shows his nose at the gratin’ you just pop him, and I’ll get up and bury him. Good night.”

“Good night, Charlie. God bless you!”

I was young then, and strong of nerve; but I did not sleep until after nine o’clock next morning.

VI.

The Locofocoville jail was a primitive structure, built of hewn logs. With the exception of the felon’s cell it was not esteemed a specially strong place of durance. Charlie used to say it was easier to get out of the old trap than to get into it. But the felon’s cell was there regarded as a masterpiece of dungeon architecture. The floor of this apartment was about two feet higher than the main floor of the building, and the space below it, clear down to the ground, was filled with solid masonry. The door was made of two thicknesses of boiler iron, strongly riveted together. The walls were lined with a single thickness of the same material, and further fortified by perpendicular bards of wrought iron placed about a foot apart and kept in place by strong staples.

About noon, the second day of my incarceration, Charlie brought in a justice of the peace, saying that he felt a little streaked about keeping me there without a regular commitment, and had brought the squire to fix up the papers. The justice advised me that all I had to do was to waive an examination.

“You see,” said Charlie, “we got the minister to make the complaint. Preachers and women always think everybody guilty. But the parson is down on mob law; so he made the complaint to have you tried and hung regular and legal. I’ll bet two dollars and a half he’s got his prayer for the hangin’ all writ out and larnt by heart. Oh, say! We’ve got Mick Mullen, the Irish hoss-thief, and I believe he’ll let some light into this case of ours. You know there’s a regular nest of hoss-thieves and cut-throats just over the county line. He don’t belong to them; he plays a lone hand mostly; but he’ll be likely to know where they are; and whatever they are, they’re the men we want, or I’m a teapot.”

I waived examination, and the justice committed me in due form. I suspected from his manner that he was of the same opinion as the minister. What little he said to me was in the severest and most frigid tone, and he looked dissatisfied and sour, I thought, at the favor which Charlie showed me.

When he was gone, Charlie told me that the popular excitement had some-what abated, but that it would still be unsafe for me to appear in the streets, and that the belief in my guilt was gaining ground because of his continued ill-success in finding any trace of the true criminals.

“You can stay in this ’ere hole,” continued he, “or you can take your chance with the jail-birds in the big room, just as you like I an’t a-goin’ to treat you like a murderer for the parson, or the squire, nor a ten-acre lot full of old grannies.”

I told him I preferred to stay where I was.

“The devil of it is,” said he, “I’m afraid I shall have to put that derned hoss-thief in here. You see, he’s a regular jail-smasher, and I might as well turn him into Deacon Smalley’s lot with a wire fence around it, as to try to keep him in this old crib anywhere but right here.”

Well,” said I, “put him in here, if you must. If I can’t stand him, I’ll let you know.”

Soon afterwards the cell was opened, and another mattress was brought in and placed as far from mind as the space would permit. Then came Mick Mullen, heavily handcuffed and shackled, and then the double iron door was closed, locked, and barred.

I was sitting at my little stand, writing by the dim light of the grated window. Mick was then a burly young fellow, with a close-cropped round head, laughing blue eyes, lips pushed forward by his front teeth, and a general expression of good-humored recklessness. He regarded the internal fortifications of the cell with a comical look of feigned despair, threw himself upon his mattress, and went to sleep.

A little after sundown our suppers were brought in. I speak of suppers in the plural number advisedly, for there was a marked disparity between the choice meal which Charlie sent me from his own table and the mush and molasses provided by the county for poor Mick. The keeper who brough the viands disappeared, and locked and bolted the door. His coming had aroused Mick. Up to that time not a word had passed between us.

“My friend,” said I, “you see they have sent me a better supper than yours. It won’t pay to insist upon knowing why. They do it, you see, and perhaps they will do it again and again. Now it happens that I am fond of mush and molasses. When I was a little boy, I used to wonder why other people couldn’t have mush and molasses every day as well as prisoners. If it will suit you, I propose that we make a mess of whatever they send us, and take our meals together as long as we both stay here.”

“Saving your presence, sir,” said Mick, scratching his head with the peculiar air of a handcuffed man, but with a puzzled air nevertheless, “saving your presence, sir, I find it hard to believe that you or any other gentleman should like mush and molasses; the devil fly away with ’em, I say. But your offer is a handsome one, and I’ll not be so ill-mannered as to refuse it.”

“Do you smoke?” said I, after we had finished our supper.

“Faith, I’d like to give up half my meat for the free use of my old pipe,” said Mick. “But the blackguards took it from me when they put me in here.”

“I have a box of cigars,” said I. “If you can console yourself for the loss of your pipe with one of these, you are welcome.”

Mick took a cigar, and managed to place it between his lips and light it with his iron-clad hands so deftly that I began to doubt whether handcuffs amounted to a serious inconvenience or not.

Before we had finished our cigars, we heard the keeper undoing the numerous fastenings of the cell door. With motions quick and noiseless as a cat’s, Mick placed his mush place and spoon on his side of the cell, so that it might appear that we had each supped by himself, and stretched himself on his mattress. When the keeper came in to remove the supper things, my fellow-prisoner was apparently in the midst of a story concerning he breaking of a colt.

When he was gone Mick resumed and finished his cigar with great apparent relish.

“I suppose,” said he, after a long silence, “you know I am in here for horse-stealing, with a fine prospect of being set up in the tailoring business in the big stone house beyond.”

“I have heard something of it.”

“It may be impolite of me, but I can’t help being half dead with trying to guess how you come to be in here, with your cigars and your matches, your pens and your paper, your beefsteak and mashed potatoes, your pickles and plum pie, and never a taste of cold iron about your clothes. I never saw the like in any jail I was ever in. It beats me [e]ntirely.”

“I gave my fellow-prisoner a brief account of the murder of my aunt and the subsequent facts which led to my imprisonment. Mick mused a long time over my story. At last he said, —

“Faith, it’s time you were getting ready to get out of this.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean this. When the grand jury come together, they will find a bill against you for murder in the first degree; then the petit jury, — bad luck to the block-heads, — they will find you guilty, and your friend Charlie will have to hang you if you don’t get away from here. That’s what I mean.”

“But I am innocent. No jury can find me guilty.”

“Can’t they, though? What ails them that they can’t? I’ve been tried for horse-stealing three times. Twice I was acquitted; I was guilty both times. And once I was convicted of stealing a horse I had never seen. Many an honest man has been hanged with far less evidence against him nor there is against you. If your neck is any convenience to you, you just take it away from here. If you leave it here long, it will be ruined.”

“But the real murderer may be found, you know.”

“True; and that’s just the only chance you’ve got if you stay here. And that same is almost no chance at all. I know who shot your aunt almost as well as if I had seen him do it. But there’s blamed little show for catching him, and no evidence against him, that I can see, if he should be caught.”

“Who was it?”

“I’ve no doubt it was Johnny Grant. The three Grants are great scoudrels, none too good to rob your aunt’s house, and fools enough to make just such a mess of it as they did. Johnny is a feeble creature and a great coward. I think it was he that shot the old lady. Either of the others would have got away from her without shooting. They are clumsy thieves, the Grants, but they are good at hiding. They know every acre of the country for scores of miles hereanent. I warrant you they haven’t been out of the woods in the day-time since the murder. But at night they haven’t let the grass grow under their feet. They’re far enough from here by this time.”

“But, my dear fellow, you talk of my leaving here as though I had only to put on my hat an walk away. Don’t you know that I am duly committed as well as yourself? Indeed, I am faster bound than you, for my case is not bailable and yours is.”

“One thing at a time. The necessity of leaving here is what we are talking of now. The means of getting away will require our undivided attention when they come up for consideration, as they say in Congress. Johnny Grant is most likely the man, partly because the Grants are the only men in this region bad enough for such a job, and partly because they have disappeared and nothing can be heard of them in any direction. Charlie hopes to get on their track yet, but I can’t see that he has the ghost of a chance, though he has sent to the city and got a regular detective to hunt for them and work up the case generally. You see he feels mighty big after catching and caging me. I sing small enough in here just now, but among horse-thieves and their good friends, the sheriff’s officers, I am a man of mark. You see I’m known far and wide as Mick Mullen, the Irish horse-thief, and yet I have been running at large where everybody knows me, a long time, because proof enough to hold me to bail couldn’t be mustered against me.”

“How, then, did you get the name of horse-thief?”

“Oh, I thought I told you before that I had been three times tried for horse stealing, and once found guilty. The time I was convicted I was innocent, and the missing horse was found dead in the owner’s back lot about a week after the trial. Meantime I had made a hole in the jail the night before the day I was to have started for the State prison. Afterwards I went back into the same neighborhood as bold as a lion. The people owned that they had been too fast, and did nothing about the jail-breaking. But the name of horse-thief stuck to me. I had to thrash three or four fellows for calling me horse-thief to my face, to say nothing of one raw-boned old blather-skite who thrashed me by the same token. For some time it was the fashion to get out a warrant for me every time a horse came up missing. After a while they gave up arresting me without proof. I hadn’t been tapped on the shoulder for more nor three years, when Charlie came and told me I was wanted the day before yesterday.”

“Take another cigar. What did Charlie want you for this time?”

“Thank you. Well, you see about two years ago I sold a jet-black gelding to a man about two hundred miles from here. I had not intended to sell the horse there, so I wasn’t disguised at all. But the man was to start for Texas in a week, so I ventured to let the brute go. Well, sir, matters took some turn that the old grampuz didn’t go to Texas at all, but stayed where he was, and kept the horse. In about three weeks the horse began to look gray and rusty loike, in spote, and he kept fading from week to week and from month to month till he was milk-white. The old lunatic that had him thought he was a great natural curiosity, and went spreading his fame far and woide, instead of passing him along fair and soft like a sensible man. The old idgeot even made affidavits that his horse had turned from black to white in less nor nine months, and had them published in the newspapers. An old neighbor of mine, who had lost a fine white gelding, happened to read an account of this miracle, and went straight to where the wonderful animal was and identified it as his own property. The old fool that bought the horse gave such an accurate account of the personal beauty of the gentleman from whom he purchases, that it all led to my being here this blessed night.

“Confound the women,” continued Mick. “There was a pretty girl in that village that did use to show me her white teeth, whenever I saw her, until I got spoony loike. It was visiting her I was when I sold the horse. I never disguise myself when I go co[u]rting, and I always do when I go horse-trading.”

“Do I understand you mean that horses can be colored so as to deceive a man with half an eye?”

“Well then, they can; but it requires an artist to do it, and he must have the genuine material to do it with; none of your stuff such as gentlemen use to turn their hair and whiskers purple and pea-green and the color of a new-blacked stove. That sort of stuff won’t do at all. A sensible baby knows better nor to pull such whiskers, for fear of soiling its fingers. You see, when I was a gossoon of a boy, I knew a quare little old woman who used to go pottering about Dublin, fixing up old boys and girls to pass for young gentlemen and ladies. I did now and then a good turn for the poor old body, and she took a mighty loiking to me. From her I learned how to make a vegetable hair-dye that leaves the hair looking natural and glossy, and soft as though no dye had ever been near it. I could make a bar’l of it for two dollars.”

“Don’t it color the skin as well as the hair?”

“’Tis sure not to color the skin if it don’t touch it. I told you before, it takes an artist to put it on. For that reason it would never be salable as a hair-dye. I can dye a horse from head to tail in half an hour so that you would swear it was born black.”

“I suppose black horses are safe from your art.”

“Indeed they’re not, then. There’s a nice decoration of my own invention that will transform a black or dark brown horse to a beautiful sorrel. It takes longer to doctor a black horse nor any other, but he’s more durable when fixed. With a little touching up now and again he can be made to last a year as bright as Busayphalus. Shearing will work wonders with the color of some horses, but that requires great care and plenty of time, and the effect is not much more durable nor dyeing. I wouldn’t recommend a new hand to try clipping.”

“How do you disguise yourself when you go to sell one of your improved horses?”

“Hardly ever twice aloike. ’Tis mighty quare, I can’t speak common English without an Irish accent, but I can speak broken English like a Frenchman or Dutchman, or any foreigner I ever saw, to the life. I can even come the Quaker dodge to perfection. I’m mighty strong as an old Irishman who speaks every word with a big brogue. I’m a fair lowland Scotchman, at a pinch, and, if I say it myself, I’m the best big Indian in America. I have a little place somewhere south of the Canada line and west of the Atlantic, where no man ever saw me, and where I keep a nice lot of wigs and whiskers and spectacles and a few clothes, and two or three tools as well. Faith, you’d smoile to see the quare lot of traps I have there, and it’s no lie I’m telling you, I made most of them myself, at odd times.

“Now sir,” continued Mick, “if a poor felly that wishes you well would tell you how to get out of this place and clean away to Canada, what would you say to him?”

“I should ask him to give me at least one night to consider his offer.”

“Very well; sleep on it, and let me know your moind to-morrow or the next day, for this is not a wholesome place, this little private apartment of ours, for men of active habits.”

We retired to our respective mattresses. I know not whether Mick slept or not. He lay still, but his breathing did not seem to me to be deep enough for that of a sleeping man.

As for me, I passed a sleepless night. I understood well enough that Mick wanted me to help him escape. Still I could not but acknowledge the justice of his arguments. The more I examined my situation, the more critical it seemed. My aunt had been killed by a pistol-shot. I had been present, armed with a pistol. I alone had seen the murderers. The slight traces they had left could easily have been simulated by me. I had profited largely by my aunt’s death. It would be readily believed that she had told me of the provision she had made for me in her will. I was a stranger in the place. There was no one there to vouch for my previous good character. My unprecedented disregard of all assaults made upon me and my paper by other newspaper men might, and probably would, be regarded by many as evidence of a cold-blooded, calculating nature. And above all, the notion of my guilt had taken a violent hold of the popular mind, consequently every circumstance would be interpreted to my disadvantage. In short, I arrayed against myself a mass of circumstantial evidence which almost made me doubt my own innocence.

Long before morning I had made up my mind to escape with Mick if I could. Having settled that matter, I managed to get a little sleep between daylight and breakfast-time. After breakfast, I told Mick I had resolved to leave Locofocoville at the first opportunity. Before commencing operations, however, I told him I must have time to write a full statement of my reasons for leaving, so that Charlie might have no just ground of complaint. Mick readily assented to so much delay. It took me all the forenoon to draw up my explanations. At dinner-time Mick confiscated all the bread and laid it aside.

“Dry bread,” said he, “is far better nor no food. We may soon see a place where a bushel of dollars wouldn’t buy a peck of potatoes. The dryest crust in life will make us proud men then.”

After dinner he asked me for a clean sheet of paper. I have him one, and he emptied the salt-cellar into it, folded it neatly, and put it away with the bread.

“You can sometimes get meat, and vegetables always, such as they are, in the woods,” said he; “but bread and salt, they’re hard to come at when you get where the dogs don’t bark.”

From that time forward, as long as we stayed in the cell, we hoarded nearly all the bread and salt that came in our way, and, thanks to Charlie’s liberality, we laid up a fair supply. At Mick’s suggestion I also laid by a small plateful of grease. After the dinner dishes had been taken away, Mick called my attention to what seemed to be a speck of dried clay upon the edge of the sole of one of his shoes.

“Just pick out that morsel of putty,” said he, “and see what you will foind.”

In picking out the putty I found the end of a minute saw, made out of the mainspring of a watch, which I drew out of its sheath in the sole-leather with ease. Upon further examination I found that the soles of Mick’s shoes contained no less than six of these little saws, some of them with teeth as fine as those of a three-cornered file, and some of them coarse enough to saw wood.

“Now,” said Mick, “if you will be at the trouble of unscrewing the buttons from the tail of my coat, you will find them mighty convenient as handles for the little saws.”

I did as directed, and found that the two innocent-looking coat-tail buttons were really knobs, admirably contrived for holding the saws, which could be readily screwed into them. I could not help reflecting that these were probably the only coat-tail buttons in the world capable of serving any useful purpose.

“Hadn’t I better cut off your handcuffs, the first thing?” said I.

“No, bother the handcuffs; I can work well enough with them on, at anything but scratching my back, and that is a luxury I can’t affoord just now. We can attend to the darbies after we leave this. We’ve got to do all our sawing while them devils are keeping up their rumpus in there beyond. It won’t do to fiddle with these things at night, at all, at all.”

“Why not?”

“Because at night every little noise can be heard. It would be loike one of them assault and battery and petty larceny pups to curry favor with the authorities by putting fleas in our ears, if we give him a chance.”

Not being willing that my fellow-prisoner should monopolize all the shrewdness and forecast of our enterprise, I took up my mattress and laid it upon his, and commenced operations upon the floor planks where my work would be hidden by my bed, when in place. Mick highly applauded this plan, and went to work diligently cutting the shackles from his ankles, in such a way that he could put them off and on at pleasure, without exposing the cut. I was almost provoked to see with what deliberation and how little haste he worked. For my part, I went at my task with such vigor that I was soon obliged to rest my aching arms and back.

“Fair and soft, my boy,” said Mick. “If you go on at that rate you’ll be breaking your heart and your back and your saw. Take your time. It’s two months and more till court sits.”

I soon learned to profit from my fellow-laborer’s precepts and example of moderation. I kept at my work steadily, but did not hurry. At the end of our second day’s work, I had sawed three of the planks twice across, between two of the joists or “sleepers” upon which the floor rested. Lifting the trap thus improvised, we discovered, as we expected to do, a mass of rough masonry under the floor.

“If the masons in this country were building prisons for their own mothers-in-law, I do believe they’d sloight their work,” said Mick, after inspecting the masonry. “This stone-work is botches, so that a full-blooded bull-pup would scratch his way through it in less nor three hours. We can move this stuff twice as fast as we could take out loose sand, without a shovel. Still, we shall need a bar to get through the foundation wall, which is decently built, as one can see from the outside.”

Mick had divested his legs of their shackles — though he still wore them in the presence of the keeper, for politeness’ sake, as he said — and was now busy cutting off one of the upright bars of wrought iron which ornamented the walls of our apartment, intending to use it for a crow-bar. He increased the labor of cutting it a good deal by sawing diagonally through it, so as to make a chisel-shaped end.

It was our uniform practice, whenever we quit work, to replace the saws in their leathern hiding-places and to screw the knobs on the coat-tails where they erst did duty as ornamental buttons. After supper Mick took out and rigged one of the saws, and resumed work, singing a dismal Irish ditty at the top of his voice to drown the noise of the saw, and continued sawing and singing until he had severed the bar. I asked him why he worked at night, contrary to the precaution he had himself recommended.

“I’ll tell you why,” said he. “I’ve made up my mind to leave this place to-night. Don’t you hear the wind and the rain? ’Tis a perfect deluge that does be coming down. There mayn’t be another such a night for traveling this sayson. The noise of the storm is elegant, and ’t is safe to last till morning.”

The little place of grease had already been converted into a lamp, by the primitive process of laying in it a slender, twisted rag, with one end extended out on the rim of the place, for a wick. At Mick’s suggestion I had made the wick very slender, so that it would make a small flame, and consume the grease slowly. At eleven o’clock by my watch we lighted our little lamp, having first darkened the grated window with one of our blankets.

In about an hour and a half we had worked our way through the loose masonry to the foundation-wall. In ten minutes more we had pried out and removed enough of the wall-stones to admit of our crawling through. We then took our store of bread and salt, my few remaining matches and cigars, and Charlie’s pistol and ammunition, rolled them up tightly in our blankets, and decamped.

VII.

A thunder-storm was now added to the rain and gale. We left the village with all convenient speed, and took a road leading northward. The storm was terrific. No living creature other than an escaped prisoner would be abroad on such a night. We made our way silently through rivers of mud. Mick led off at a great pace, taking the middle of the road. I kept up with him without difficulty, for I was then a first-rate pedestrian. Occasional flashes of lightning showed us our whereabouts, and enabled us to keep the road. Hour after hour, and mile after mile we went along, splash — splash — splash! the track getting deeper, all the way, until suddenly the storm ceased and the sky cleared, just as the day was beginning to dawn.

We now found ourselves passing a farm-house. A little iron kettle stood just outside the kitchen door. Mick confiscated it, and, signing for me to follow, made straight for a piece of woods which lay back of the house. As I passed the house I deposited two half-dollar pieces on the ground where the kettle had been, determined to keep clear of downright larceny while my money should hold out. By taking a somewhat tortuous route we managed to avoid clearings and still make our way northward until about an hour after sunrise. It then became impossible to travel further without passing through an open field.

Having ascertained that fact, we retired into a dense thicket and threw ourselves on the ground. It was now early in August. The day began to promise a degree of sultriness which was truly grateful to us, drenched and chilled as we were. Mich then produced a saw with very fine teeth, which we had not used. With this excellent implement I soon relieved him of his handcuffs. These tokens of captivity we buried. Fifteen years afterwards they were plowed up and brought to my office to be noticed in my paper as local curiosities. I crawled to a sunny spot, a little opening in the midst of the thicket, and laid me down to dry, and if possible to get warm.

“That’s right,” said Mick. “Go to sleep and I’ll watch. When you have finished your nap, I’ll trouble you to keep a lookout while I take a couple of winks.”

I was soon asleep, and did not awake until after noon. When I awoke Mick threw himself on the ground and went instantly to sleep.

I had now nothing to do but to sit still and wait for night to come. How was I to get through the five remaining hours of daylight? My first resource was to count my money. I found that I had with me a little over forty-three dollars. I next cut a very crooked and gnarled beech stick, trimmed of the branches and knots as neatly as I could, and gave it a curiously mottled appearance by chipping away little pieces of the outer bark, so that the spots were disposed in irregular spirals — a style of walking-stick then much affected by youngsters. I then cut and ornamented in like manner a straight beech shillela[g]h for Mick; and was studying what next to do, when Mick awoke.

“Have you looked at the pistol?” said he.

“No, and I was just racking my brains for something to do.”

I drew the charge from the pistol, cleaned it thoroughly, and reloaded it. It was now dusk. Mick helped himself to a small crust, lighted a cigar, took the blankets down from a bush where he had hung them to dry, and wrapped them artistically around our small supply of other movables, including the little kettle, so as to make a compact bundle. He tied this up with a cord which he had manufactured out of moosewood bark, while I slept, slung it across his broad shoulders, took his shillela[g]h in hand, and announced that the time had come for starting.

We crossed a narrow field and took the highway, this time in a westerly direction. We walked at a leisurely pace until we reached a road which crossed the one we had been traveling, at right angles. Mick, to my astonishment, turned to the south. As I was utterly ignorant of the country I was fain to follow where he led.

“How are we ever to reach the Canada line by going southward?” said I.

“This road goes through a sheep-raising neighborhood,” answered Mick.

“What do we want of a sheep-raising neighborhood?”

“They keep no dogs down here. They don’t know enough about their business to keep shepherd-dogs, and they know too much to keep any others. The dogs have been barking at us ever since we started. There’s three of them at it now, fit to split. It will relieve my nerves to be out of hearing of the brutes.”

Having no great respect for the delicacy of Mick’s nerves, I was not quite satisfied with this explanation; but feeling sure I should get no other at that time, I trudged along in silence. In about half an hour we were free from the baying of watch-dogs. Suddenly Mick seated himself by a large hemlock stump. The moon had been up some two hours, and was shining so brightly that one could read coarse print. Mick deliberately opened his pack, produced our little store of dry bread, took a piece for himself, and advised me to eat a bit.

“You see,” said he, “one can’t make a Christmas dinner of this stuff all at once. Little and often is the way to keep up your strength on brickbats and rusty nails.”

“I am a good deal more thirsty than hungry,” said I.

“What an idgeot I am!” said Mick. “There’s an elegant spring not more nor a quarter of a mile from here.” He tied up the bundle again, leaving out what bread he supposed we should need for that occasion. In a few minutes we reached the spring, which was situated about midway between the road and a fine farm-house, and not more than three rods from either. Here we refreshed ourselves with dry bread and excellent water, and concluded our repast with cigars. While we were smoking we heard a distant clatter of hoofs. Instantly Mick was on his feet and making his way to an embowered summer-house in a garden near the farm-house. I followed, and we were soon seated on a rustic bench, where we could by careful peeping command a view of the road without being seen. Two horsemen soon came, dismounted at the gate, went to the spring, and drank. As they were talking quite freely, we recognized them as deputy-sheriffs, in search of us. They soon remounted and rode northward.

After they were gone Mick relighted his cigar, saying composedly that he had fully expected that we should encounter sheriff’s officers that night; but that as they were sure to be on horseback and to ride so that they could be heard for half a mile or more, he had had no fears of being seen by them.

He then astonished me by dividing his soft felt hat into a hat and a helmet, or night-cap, as you choose to regard it. The latter had been a hat, but was divested of its brim so neatly that when drawn over the unmutilated one the whole structure exactly resembled a single homogeneous hat, of the most common and unstudied character. Between the two there were found bank-bills of various denominations to the amount of two hundred and fifty dollars. Mick transferred twenty-five dollars to his vest pocket, replaced the balance between the hat-crowns, readjusted the divided chapeau, and put it on his head, remarking that that was the way to make a hat sunstroke-proof.

We went into a piece of woods that lay about half a mile west of the house, and made our way slowly westward until morning; and then started once more due north through a trackless hemlock forest. Owing to the prevalence of west winds in this country the topmost twig of nine hemlock-trees out of ten inclines to the east. This and several other sylvan means of determining the points of the compass were taught me by Mick as we proceeded. After we had tramped through the woods some two hours by daylight, Mick directed my attention to a large gray squirrel.

“That felly,” said he, “for all his foppish ways, would help our dry bread a good deal. Will you try the pistol?” I was glad to see an opportunity of rendering essential service in our flight. I am a natural marksman, and I brought down the squirrel at the first shot. As soon as we reached some decently clear water we boiled the squirrel in the little kettle, with some dry bread, and some roots selected and gathered by Mick. This breakfast was a huge success, if enthusiastic appreciation is just a measure of success on such occasions. After breakfast we slept and watched two hours each. We then took up our line of march again due north. During the afternoon I was so fortunate as to bag another squirrel and a partridge. Night found us in the edge of a dense cedar swamp.

VIII.

This swamp was a great triumph of Northern vegetation. It bore a dense, tangled profusion of everything that grows upon low lands in this latitude, and here and there, upon slight elevations were luxuriant growths of upland trees, shrubs and humbler plants. To one of these elevations we made our way across a quaking bog.

The mosquitoes had troubled us a good deal, that day and the night before. Now they swarmed about us like angry bees, and threatened to consume us.

We lighted a big fire at the foot of a great elm-tree, and numerous smaller ones all around. These latter we partially smothered with turf, in order to make them yield as much smoke as possible. At first it seemed as though the mosquitoes could stand more smoke than we. For some time after lighting our fires, every step we took among the thick vegetation seemed to stir up and provoke to the attack a numerous and hungry swarm. But when our smudges had been playing upon them half an hour or so, the music of their tiny bugles became fainter, and, as the cloud of smoke extended itself farther and farther into the swamp, they gradually ceased to annoy us.

Having procured some passably clear water from a neighboring pool, we dressed our game and cooked it, ate what we needed, and left the rest for breakfast. After supper we spread our blankets near the fire, sat down upon them, lighted our cigars, and betook ourselves each to his own meditations.

The fire-light shone in a bright streak along the nearest side of each surrounding tree, leaving the rest of it in such black darkness as to suggest the notion that some creature might be lying securely in ambush in each great shadow. The play of the light upon the lower side of the verdure overhead tinged the various shades of green with an unwonted ruddiness. As the fire gnawed its way through the thick bark of the great elm and fastened upon its sap-wood, it seemed to be repelled by frequent little angry explosions or “snaps,” sounding like the cracking of percussion-caps. There was not a breath of wind astir, but the woods seemed full of noises. I was every moment startled by the breaking of sticks, and the sound of what seemed to be approaching footsteps. Strange calls and cries from birds and beasts began to be heard as the evening deepened into night.

“What’s that?” whispered I, referring to light but unmistakable footsteps close at hand.

“’Tis some foolish beast reconnoi-tring. The silly creatures are mortally afraid of a fire at night, and yet they can’t help prowling around it.”

“Then we are safe from four-footed visitors while we keep our fires burning, are we?”

“Yes; they’ll keep pottering about close by us; but they won’t come near enough to show us the color of their eyes.”

Mike collected and disposed near the fire a luxurious and fragrant couch of hemlock and cedar boughs, upon which we spread our blankets and reposed our weary and mosquito-bitten bodies. It will be remembered that we had each taken a pretty substantial nap that day. We were therefore not drowsy, and we put far from us the question who should first sleep and who watch when the time for sleeping should come. There was near us a pond or pool full of noisy bull-frogs. They seemed to have for leader a basso of great power and profundity.

“That old felly moinds me,” said Mick, “of an old chap in Philadelphia who did use to stand on the docks when the steamboats came in, and keep saying from the bottom of his stomach, ‘Globe Hotel, Globe Hotel, Globe Hotel.’”

“You’ve lived in Philadelphia, have you?”

“Yes, indeed. I was there more nor a year. It’s a drowsy old place, by reason of the streets cutting one another square across, like the lines of a multiplication table. The houses are mostly all aloike, and every house has a nice nurse-maid, leading two nice children up and down in front of it.”

“Mick,” said I, “when did you leave Ireland, and why? Tell me all about yourself. I’m dying to hear your story.”

Mick went to the cigar-box, now running low, took one weed for himself, and tossed one to me. When we had them lighted and were once more upon our couch, each with his head resting on his elbow, Mick proceeded: —

“I suppose I was born in Dublin, though in what corner or cellar or garret I have no idea. My first recollection is of leading an old woman around the streets, who pretended to be blind, but could see like a cat. She called herself my grandmother. If that was true it was the only truth I ever heard her tell. She begged in the streets, and did a little in the way of looking up good jobs for the burglars. We lived in a cellar in the thieves’ and beggars’ quarter. Old Mag Runnells — that was the old woman’s name — was quite a character there. People who feared the police, or who had stolen something bad to hide or hard to sell, used often to come to her for advice. They always brought with them a bottle of whisky, for devil a word would old Mag say till her whistle was wet. Sometimes a man or woman of our set would want to borrow a small sum of money of her, and would bring some valuable to be left in pawn for the loan. She would say, ‘Go away wid yer bawble, and don’t be cracking yer jokes on a poor old blind body. If ye’ll come back in an hour, maybe I can find some pawn-broker where I can spout it for yees.’ Then she’d send me off to play, and while she was alone she would get the money out of some hiding-place she did have somewhere.

“She was not very hard on me. I must say that for her. She did cuff and bang me about a good deal when she was out of sorts or drunk, but she fed me well and clothed me comfortably, and taught me to read and write and reckon; for she was quoite a scholar, and had done something at forgery in her day.

“It would have edified you to see the old woman and me on our rounds in the streets. She went always in black, thread-bare clothes, with never a speck of dust on them, and the whitest and stiffest starched cap in all of Dublin. She did look as decent as a church-warden’s widow. Her quare old eyes stared straight before her. She looked blinder nor a wooden god and older nor the Lord Lieutenant’s castle. I wore nice, clean, patched jacket and trousers, and a close-fitting skull-cap. Oh, but wasn’t I the meek, dutiful little grandson, leading his poor blind grandmother, and didn’t I know how to blarney the kind gentlemen and beautiful ladies! We didn’t waste much time on the citizens, but devoted our attention mainly to the country gentlemen and country traders and their good wives, who almost always gave us something. We were the best beggars in Dublin. Old Mag used to say that, if one had a talent for it, begging was far more profitable nor stealing, to say nothing of the danger. Sure, the old body had a right to know, for she had tried both. She had been in jail I don’t know how often, and had spent fourteen years at Botany Bay.

“Sometimes we would go into a house or shop to beg. If we got nothing else we were sure to get an observation of the premises that might be useful to the burglars. I believe Mag’s only notion of honor was that it would be a scaly trick to report a house where the people had given her silver, to the burglars. But woe to those who gave her nothing, or coppers, if there was anything in the house worth stealing.

“These same burglars did use to borrow me now and again of a dark night, to lift me in at windows and poke me through holes where a man couldn’t go.

“One morning when I was about ten years old, or maybe eleven, I lay in my bed of rags in one corner of our cellar long after I had waked up, wondering why the old woman didn’t call me as she used to do. At last I crawled out of my own accord, and went to see what ailed the old body. She was dead. I was a sharp little devil, and hunted the cellar through for old Mag’s money, before I called the neighbors. I only found a few shillings.

“Homeless and penniless, I had no resource but to beg and steal in a small way, on my own account, and to help the burglars when they chose to employ me. I ate whatever I could lay my hands on, and slept wherever I could find shelter. Now and again I would make a little raise and buy me some decent second-hand clothing, but most times I was the dirtiest and raggedest little vagabond ever seen out of Dublin. There were thousands of us little outcasts there, all bound for the gallows or Botany Bay, or some such end.

“When I was thirteen or thereabouts, I went to learn a new trade. My handiness at opening doors and windows from the inside, after I had been helped through a sash where a pane of glass had been taken out, attracted the attention of an eminent manufacturer of burglars’ tools. His name was Durfee, and he was the most impudent rogue in all Ireland, I do believe; and that same is saying a great deal for him. His shop was on a respectable street. He pretended to be a gunsmith. But his real business, what kept his forge blazing and his hammer clinking and his file scraping in the little back shop, was making burglars’ tools, and such-like deviltry. No man could harden a bit of steel harder nor he could. He was mighty handy, too, working with other metals. He made splendid gold rings for pickpockets, with beautiful little spring-blades in them, elegant for cutting pockets with. He was the inventor of a nice little circular saw which wound up like a watch, and would cut off a steel bar an inch thick with one winding; price, fifty guineas. I had the honor to discover an improvement in this beautiful implement, by which the number of revolutions per second could be doubled without increasing the size of the toy. I have one of them hidden in the heel of my left shoe now. If the saws we used up at Charlie’s hotel, beyond, hadn’t been better for the coarse, easy work we had to do there, we should have had recourse to that same.

“Durfee’s wife’s brother was a policeman, and lodged with us, and I do believe the honest fellow never suspected that his brother-in-law made anything worse nor elegant dueling pistols, for which he was famous far and woide. I stayed with him until I was about seventeen. Then he, having made a poile of money, bought a nice place about fifteen miles from Dublin, where he set up for a country gentleman and was made a justice of the peace. Before that time I had learned the art of coloring hair, from an old woman I told you of, and out of pure mischief had tried it on several cats and dogs, and always with perfect success. The idea got hold of me that the art might be applied profitable to horses of the wrong color. Horse-stealing in Ireland is not so easy a business as it is here. Still, it is followed there to some extent. There was always in the thieves’ quarter in Dublin two or three horse-thieves from the country, stopping there for their health. I got acquainted with one of these — one Johnston by name, a hard-riding, hard-drinking, red-nosed old vagabond. When he could be kept sober, he was the greatest horse-thief in Ireland. He had no skill in disguising horses, but he could disguise himself beautifully. He could take any character, from that of a colonel of dragoons to that of an old woman, to the life, and it was said among his admirers that he could change characters with his horse on the run. His plan was to steal a horse in one guise, sell him another, and spend the money in his own proper character. When he and I joined forces I brought my art of dyeing horse-hair into play, and we did a fine business for a few months. We went all over Ireland, and extended our operations into England and Scotland. You see, when a horse has changed color, you can go leisurely and sell him in the best market. We might have done a fine business, but poor Johnston would get drunk. I ran two narrow chances of being arrested and transported, through him, and one day he did get himself in limbo in a country jail in Wales. I smuggled in to him all the jail-breaking machines I had with me, and left the place. What ever became of him I don’t know, for just then the whim seized me to come to America, and I went straight to Liverpool and sailed for Philadelphia in the first vessel that cleared for America.

“I operated at house-breaking a little while in Philadelphia. One night an old Quaker wake up unexpectedly. He was a mortal big old broadbrim. ’Tis no lie to say he was bigger nor you and I both of us. He dropped down on me like a terrier on a rat, and do what I would I couldn’t get out of his clutches. I barked his shins and blacked his oise splendidly. He wouldn’t strike back, but he wouldn’t let go the grip he had on me, nor stop crying ‘Police! police!’ till I was half-strangled, and in the station-house — bad luck to it for the dirtiest, noisiest, most uncomfortable place that ever a poor devil spent a night in. It happened that I was out that night in the character of a long-haired, big whiskered Frenchman. I was dressed in a suit of black broadcloth worn smooth and shiny, such as seedy foreign gentlemen mostly do wear, and I pretended to be taking snuff every five minutes. The police searched me carefully and found nothing but my snuff-box and a pair of spectacles. In the morning I was examined before some sort of a city magistrate. I don’t know how he was called. I spoke the worst English with the best French accent I could. Old Broadbrim and his family appeared against me. Well, he told them how he caught me and held me, and how I smote him many times and in divers places, trying to get away from him, and how he was sorely tempted to smite me in return. The people in the court-room all laughed, but they seemed to be laughing more at the Quaker nor me. His catching and holding a burglar seemed to be looked upon as a mighty good joke upon him.