Miss Larkspur’s Diamonds

by Hester Bittersweet

She took her place on the witness-stand, looking, like most people in such a position, unnecessarily decided, and yet not a little overawed and at a disadvantage.

“Miss, or Madam, what is your name?”

“My name is Honoria Grimshawe.”

“Where do you reside?”

“I live, during the school year, at Button High School, in the outskirts of this village.”

“Were you at Button High School on the night of the late burglary at that place?”

“I was there at that time.”

The substance of Honoria Grimshawe’s remarkably clear and explicit testimony touching the disappearance of Augusta Larkspur’s diamonds, was what follows:

“I have known the accused, called Dim Dark, for some months. I first met her on the opening of our spring term last April, when she applied for admission to the academic department of our school, and was sent to me to be classed in primary algebra. She gave her name at that time as Sarah Barker.

“I was with our young people on what we call Recreation Evening, which was the one immediately previous to the robbery. We had tableaux that evening. I assisted in arranging them, though this was not my regular business, but that of the head teacher, Miss Hester Bittersweet, who was ill that night. The representation consisted of palace scenes, and required a great deal of sparkle to render it effective. All the jewelry in the institution was gathered together for this occasion.

“I was very particular about everything. I made an inventory of all the articles brought in for use in the tableaux, affixing the name of the owner to each, as was Miss Bittersweet’s custom. I was specially precise about the jewelry; things of this description are liable to be lost on such occasions, or at least changed about.

“When the first bell rang, at half past nine, that evening, I desired the young ladies to disperse to their rooms. They did not go at once; Dim Dark began to give out conundrums, which stopped them.

“Half an hour later the ten o’clock bell sounded. I then ordered all the young ladies to their beds immediately. Augusta Larkspur, Georgiana Mixer, and some others, went away grumbling. Miss Larkspur, in particular, was unwilling to leave without her diamonds.

“The tableaux were arranged in Dim Dark’s room; that was No. 5. As soon as the pupils had gone out of it, I commenced gathering up the jewelry, after which I conveyed the entire collection to my own chamber, and sorted it out there. This took me some time.

“I deposited the whole in the upper drawer of my dressing-bureau, placing the watches together in one box, the chains and bracelets in another, and so on. The sets I laid away by themselves.

“I intended to lock Augusta Larkspur’s in their own casket. It was there with the jewels. It is a double casket of elaborate workmanship. On the outside it looks like a block of rough iron. Within there is a silver box lined with velvet. The two parts of the jewel-case are united at the bottom, but have separate fastenings. The outer, iron shell unlocks at the side with a little round key; the inner shuts with a concealed spring in the back. This spring works very hard indeed.

“Both portions of the casket stood open, and I took it into my hand, in order to examine the spring. Accidentally, somehow, I snapped the silver box together, and I could not manage to open it again.

“I then enveloped the diamonds in cotton, and wrapped a scrap of blue silk out of my ribbon-drawer about them, which I gummed fast together for safety. This made a soft, flat packet, resembling a very thin cushion. I deposited it in a small sandal-wood box of my own, and placed the latter in a drawer with the other articles. I locked the drawer, and slipped the key under the edge of the carpet at the head of my bed, where it was found when we looked for it after the departure of the robbers.

“Immediately afterward I locked the door of my room, tried to bolt it, but failed to do so, something appearing to be wrong with the catch, and retired to my bed.

“My watch, which was not deposited in the box with the others, but was hanging in its own case at the head of my bed, was stolen also.

“I think I fell asleep very soon, being quite tired out, and feeling no apprehension of thieves. Did not hear any one entering the room, nor moving about in it, nor in the halls. Was not disturbed in any way, until Miss Bittersweet called me up after the robbery, to look for our valuables.

“As soon as I awaked, I saw my sandalwood box standing on the top of the bureau, with, the cover off. The upper bureau drawer was pulled out a little way, having things dragged out of it. Then I said, ‘They’ve taken the jewels.’

“Miss Bittersweet ran to look closer, and found that both the drawer and my box were quite empty. I have not seen any portion of that jewelry since.

“I have been shown a discolored silk rag, found at Button High School, in the studio, immediately after Dim Dark was brought up from the paint-cave and handed over to police. It might have been withdrawn from her mouth with the gag. The color appears to have been discharged from it by continued chewing, and it is much frayed and worn. I cannot say certainly whether or not it is that in which I wrapped the diamonds. It might be the same, and it might not. The general size and shape of this scrap are like those of the bit I used.

“I am not a judge of jewels. Miss Larkspur gave us the impression that these were uncommonly valuable. She first brought them to Button High School, when she returned from spring vacation on the first day of last May. This was after the session had been opened rather more than two weeks.

“Miss Larkspur stated to us, at the time, that the diamonds had been left to her by her uncle and guardian, Captain Augustus Larkspur, for whom she had been named, and who had recently died on a return voyage from India.” And so on.

Dick Masters, of the detective force, was the next important witness examined.

Mr. Masters resided at Chicago. Had been a resident at Button High School for some months, was there disguised as a pupil in the capacity of detective, etc., etc. At about half past eleven on the night in question, he unlocked the door of Miss Grimshawe’s room with a key of his own, entered, and concealed himself in a certain wardrobe, which he had previously fixed upon for this purpose. He left the door of entrance locked as he had found it.

Between an hour and an hour and a half later, perhaps, Dim Dark came into the room and proceeded at once to the dressing-bureau. Both this piece of furniture and the wardrobe stood obliquely in angles of the room, the former occupying the northwest, and the latter the northeast corner of the apartment.

Dim Dark then appeared to be fumbling with the bureau drawer for a minute or two, but was invisible to Mr. Masters. The first he actually saw of her, she was standing beside the drawer, which was open, and which had a dark lantern within it already lighted. She had a gray wrap about her person, and what seemed to be a gray wire mask on her face. She directly proceeded to remove the contents of the drawers, and pack them into a carpet-sack she had with her.

Mr. Masters saw the accused take the diamond casket from the drawer, inspect it closely, and then place it quite by itself, behind the swing mirror of the bureau. When she finally discovered the sandalwood box, she gave it a shake, opened it, and removed the blue silk packet, which she squeezed in her hand and tore open a bit, and the contents of which she closely scrutinized. With this packet still in one band, she removed the casket from behind the mirror with the other, and deposited it in the carpet-sack. Mr. Masters did not see what became of the packet, paid no particular attention to it, supposing the diamonds were enclosed in the casket.

Witness saw Dim Dark take possession of the watch hanging at Miss Grimshawe’s head. Saw her leave the room, carpet-sack in hand, with the lantern still lighted, but burning low. Did not see nor hear Miss Bittersweet behind him. Followed Dim Dark closely through the halls, slipping from doorway to doorway. She walked slowly and carefully, did not stop either in her own room or elsewhere. Went straight to one of the studio windows, unbarred it, and handed the carpet-bag to a man who stood outside and reached in his arm for it. The man took the dark lantern away.

A melee followed, during which Mr. Masters and the accused were precipitated into the paint-cave together, where they remained until brought out by Detective Hansleigh, etc., etc.

Miss Augusta Larkspur was present at the close of the trial. She sat with me. We had the honor, I recollect, of being blandly revolved about by the local beau of the day, a philosopher named Hare, who practised law in town, and adored beauty—with a fortune.

The trial proceeded to a speedy issue, the facts accomplished being, the gang in general brought to grief, and Dim Dark sent up for— I think it was twenty years. At any rate, she died while in prison.

That evening, Mr. Dick Masters, detective and bachelor, walked home from the courthouse in our company; Lawyer Hare devoting himself, in particular, to my pupil, Miss Larkspur.

Presently, Dick Masters and myself fell behind the crowd a bit.

“I’ve a rather ugly piece of business to discuss with you, Miss Bittersweet,” says Dick, “if I may.”

I thought he might.

“Precisely! Now then! Walk slowly, and I’ll drop the subject at Button High School gate. Miss Larkspur’s diamonds are lost.”

“Why, so is all the other school jewelry lost,” I said.

“Not lost to police, it never has been lost to us. But the diamonds are. They were not brought in with the other booty, police can’t find them; can’t guess who has them; don’t know where to look for them. They are absolutely lost—gone.”

“Gone!” I cried, aghast. “They are her whole fortune. What is to be done now?”

“Well,” says Dick, “what’s to be done now, is to institute an organized search for them. That’s what! Hansleigh and I have shaken hands over that. Our great Diamond Case, we call it,” says Dick, with a laugh.

“Poor Augusta!” I sighed.

“Poor Augusta, indeed! I don’t mind telling you, Miss Bittersweet, you being her best female friend, that I am sworn in my heart to stand by that lady.”

“Walk slower, and I’ll map the case out for you a bit,” Dick went on. “Now mark me! There are two lines of work open to us. —Say Dim Dark has made away with those diamonds, herself. —Say the gang did it.

“Hansleigh takes the latter view. Hansleigh says—well, this and that. No matter what! But that’s Hansleigh.”

“Needn’t talk to me,” says Dick. “That she-robber, has hidden the jewels somewhere! There’s not her match in the gang for plotting and counterplotting. Bless you, no! Nor in any other gang that ever I knew anything about. Well, that’s me, now.

“Why, look at it once. She takes the diamond casket out of the drawer. She believes the jewels are in it. But what! Does she pack it like the other booty? —No sir! — (a figure of speech.)—She puts it carefully away by itself, not meaning it to pass into the hands of her accomplices. There it lies till such time as the blue packet comes to light. Then, mark me! —when she knows the casket is empty, she crams it in with the other plunder. And what she does with the blue silk packet the Lord only knows.”

“Might she not have secreted it about her person?”

“Not possible! Had been searched by experts in the highest style of art.”

“Why not scrape the paint cave, then?”

“Done! a month ago.”

“Well, that’s where I am at present,” concluded Dick Masters, “and here is Button High School at hand.”

“They’re in the building. Right here!” says Dick, stamping. “And somebody knows where. Likely to be a man. Call him Bogles. Bogles is not one of the gang, we may be sure. She has robbed the gang as well as the school.[”]

“Now for your instructions! I may count upon you for help?”

Assuredly he might do so.

“Only this. Keep dark, and look alive for Bogles. He’s somewhere; and he’s coming. You are sharp, and it is your business to look out for him. Au revoir.”

With that Dick made me a stunning bow, and off he trotted, vanishing from town, and being popularly supposed to have taken final flight from those parts.

In the course of time and law, we Buttonites came once more into possession of our stolen property—all of us, at least, except Augusta Larkspur. Miss Larkspur was in consternation at her loss, quite naturally; so, indeed, were the whole school, through sympathy, Augusta being a general favorite and pet. She was an orphan, entirely dependent upon her uncle’s bounty, and the jewels he had left her comprised the bulk of her fortune.

One evening, not long afterwards, we were pacing through the great hall on our way to prayers in the chapel, when whom should I espy but Mr. Dick Masters again, standing in a recess under the stairs, and exchanging how-d’ye-do’s with his former schoolmates. Not at all orthodox, perhaps, but extremely lively and agreeable. As usual, I came last, frowning down loiterers by the way.

Dick did one of his gallant bows to the knot of girls immediately preceding me, and received return demonstration in a hurricane of smiles and nods. Then he put out his hand, and asked me to stop a bit.

At that instant, Augusta Larkspur, all of a glow, came running down the stairway over our head, bringing a book, for which she had been despatched in hot haste by our Great Mogul in music, Professor Thprsehkw-z-x—I never could pronounce his name, much less orthographize it.

Mr. Dick hoped he might detain the lady a moment—only a moment. Not, as it turned out, that Mr. Dick had anything official, or even important, to communicate, by no means. He felt hearty sympathy for Miss Larkspur, that was all.

“Having been one of you,” he remarked, with an uneasy laugh—

“O, la! hold your tongue, do!” cried Larkspur, rosy red.

His little sentiment successfully achieved, Mr. Dick mopped up his forehead, waded through and through his front hair, and subsided. It was high art, of course, but decidedly not in his line.

Georgiana Mixer, meanwhile, appeared at the chapel door and beckoned our party in. Professor Button was just reading off the last verse of the evening hymn, and Augusta was always counted upon to lead in the singing.

She had a remarkable voice, rich and powerful. In fact, there had not been its like at Button High School for years.

“Take heart!” cried Dick, in grand finale. “Take heart and keep heart, my dear—my dear, ahem! young lady.”

“Whose?” inquired Georgiana, in a stage whisper.

“We’re going to sing, ‘I love to steal,’ tonight. Dim Dark’s favorite, I believe! The Sal Volatiles are to make a dead stop after steal, you know, and do three terrifying groans. Don’t you undertake to interfere now, Larkspur, I warn you.”

“La! well, here is Miss Bittersweet,” replied the other. “You’ll remain, Mr. Masters, till we come out again? —You cannot? —Ah, dear me! How unfortunate! Good-by, then—good-by!” And away the pretty pair of silly young things flitted, smelling horribly, if I must say it, of kerosene oil.

Dick uncovered himself, and stood with bared head and folded arms till the sweet voices and the magnificent one died away in stillness, without the groans. As for me, Hester Bittersweet, I might have been in Lapland, or the Feejee Islands, wherever they are, for all Dick Masters; or, better still, in the chapel.

I knew what was going on there well enough. The Bittersweet cat being away, the Sal Volatile Secret Society were out in full parade, improving their privileges as mice, preposterous and irrepressible. In a minute more Professor Button would be distractedly dashing through prayers, open-eyed, to catch somebody doing something.

“Anything from Bogles?” says Dick, at last, grim as a graven image.

“Nothing, Mr. Masters.”

“Sure?”

“Yes.”

“Stranger here? or been here? Old-clothes-man?”

“No, Mr. Masters.”

“What’s Hare about?”

“Ambidextering, as usual, Mr. Masters. Don’t be hard on him.”

I always make a moral suggestion when I can, hit or miss. It is a way I have fallen into at school.

“Hare’s a blundering fool!” poor Dick blurted out.

“Ah! do you think so? You’re a famous sweetheart then, to yield him up the key of the castle like this! Never to open your mouth to the lady, with him coming and going, month in and month out, and playing pick and choose, and fast and loose. I’d not look at either of you, if I was Augusta.”

Dick groaned, muttered something high and mighty about not wanting to bring the lady to poverty, and silently withdrew his forces. Mr. Dick had other business in town. He desired to establish secret headquarters at Button High School, for say a month, say six months. He could not be certain for what length of time, in fact. He wished, in particular, to leave a few traps in a safe place somewhere. Preferred to deposit them within my own special jurisdiction. Any dry outer spot would serve the purpose, provided he could have access to it at all times; in the night, for instance.

We fixed, at length, upon the woodchest in my recitation-room as a suitable hiding place. I kept this apartment locked when not using it, carrying the key in my pocket; but Dick could, of course, duplicate the instrument for his own purposes.

The wood chest, a box about four feet square, was constructed in one corner of the room, contiguous to a stairway leading to the attic. One end of the box, projecting some three feet behind the wall, passed underneath the stairs in question, as far as the width of the latter would allow, and then, turning a right angle, extended lengthwise to their foot. Here Dick contrived a sort of sliding panel, which opened into a small enclosed space beneath the two lowest stairs of the flight. The false, or back wood chest, besides being close and dark, was usually half filled with debris and unmanageable fuel. Further, the place was infested with ravening cockroaches. Further still, one could only reach the secret opening by writhing to it like a serpent. And finally, when you did reach it, the panel defied detection. So far, sogood.

“I say! you recognize this?” says Dick, by-and-by.

He was in the act of folding a gray coat of some heavy stuff, rather behind the fashion as to style. It had a long body, cut to fit over the hips, with a very short skirt, about ten or twelve inches in length.

“Recognize it? Not a bit?” This after mature inspection.

“Not! come, now, that’s good. You ought to know it every time.”

“Indeed!”

“Had it on night of burglary. Sheep’s gray, you observe.”

Sheep’s gray! dear me, so it was, the very same. I did not see it, of course, when Dick was shoved into the paint-cave with his lady prisoner, the studio being dark; but I particularly noticed it when the two were brought out in the morning. Dick was packing it away now with other traps, as a sort of reserve suit.

“Haven’t had it on since,” he pursued; “but all the better for that.”

“As a disguise,” I assented.

“Precisely. You’ll drop a line to a fellow, Miss Bittersweet? In case anything should turn up, you know.”

“But where?”

“O, well, anywhere. Right here, for instance, on the west blackboard. At top, high up, in algebraic cipher. Write after it, ‘Don’t rub out.’”

“And you can’t be too careful, Miss Bittersweet,” says Dick. “I’m watched.”

“By whom?”

“Lord love you, how do I know? Don’t know who he is. Can’t make out what he’s after. He follows me, that’s all.”

I suggested Bogles.

“Perhaps! but, then, why does he dog me? I haven’t got his diamonds. He may be watching police through me, but I don’t believe it. He’s welcome, anyway. Only do you look alive.”

I registered a very sincere mental vow to do so.

“Brings a lot of trumpery, brackets and trash,” Dick pursued. “Trades ’em off for old clothes. Gets into rooms to put up brackets. Makes acquaintance with servants, and that. The fellow has been lying low for a day or two, and I thought he might be here.”

No, he was not.

In the meantime, Augusta Larkspur’s single great misfortune was culminating in a host of petty everyday miseries. Her friends changed—at least many of them changed; among the number, Lawyer Hare, a favorite suitor, who was by common, not to say mutual understanding, to have married her out of hand.

Nobody would say, however, that Lawyer Hare had fallen short in his gallantries. He was, on the contrary, impressively attentive. In fact, he was most oppressively so, managing effectually to quench the incipient young flames always hovering about Miss Larkspur’s beauty. He paid, in brief, full tribute of conventional mint and cummin in the Larkspur tithe-granaries, but—

Well, he got no further, as he decidedly should have done, under the circumstances.

“Lawyer Hare understands most things,” said Augusta, one day, in a pout, “except always how to press an advantage.”

I fell back upon my privilege, as an ogress and a Tartar, and called my fascinating pupil to a point-blank account. There was no one else to do it, observe.

“I think it high time for your friends to interfere,” I remarked, with emphasis.

She laughed at me.

“I don’t like you in that vein, my dear.”

Then she stood up, laid her head upon my shoulder, and fell a sobbing:

“La!” cried she, “and so here’s my darling Bittersweet, to look out for a poor girl, and scold her well when things go amiss, though she hasn’t a penny.”

Ready enough at scolding; but would she, or would she not, bring that poor-spirited limb of the law to terms, was what I begged to be told.

“Goodness gracious!” answered Augusta, fluttering back into her artificial ways. “You have such a superior talent at putting things, you have, indeed, Miss Bittersweet.”

I drew a little twisted note from my pocket, and tossed it into her lap.

“I suppose it is from him,” said I, grimly.

“Ye-e-es!” opening the sheet with a flush. “An invitation to the literary masquerade. I may go, Dragon, I hope?”

“Most unequivocally not.”

The witch giggled. Clear schoolgirl.

“No? dear me! Here comes my prince, a galloping to fetch me in his golden chariot and eight, and the dragon refuses him entrance.”

“The true prince will bring a heart in his hand. Fair Star. By that token he may come in.”

Then, hard pressed, the brilliant creature sparkled out at me in a look which set my mind at rest.

“I’m not an angel, Dragon, so there, now! that’s flat! Don’t you set me down for an angel, no, nor a fool, no more!”

I was only too glad to set my lady down as a high-spirited one, who resented the vacillation of a double-dealing lover, and intended to punish him for the same.

An excitement awaited me the very next morning in class-room. The following, on the west blackboard, at top, high up, followed by, “Don’t rub out:”

312 p+87 z i k=9 l i+y l t o v h—g l+w z b. n v2 g+n v+g l=m r t s g.

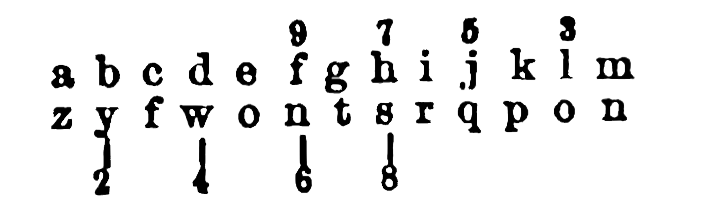

An algebraic cipher, plainly. I locked the door, took out a bit of crayon, and wrote beneath the inscription the following key, fixed upon by Dick Masters:

Under this again the message deciphered: *

Look sharp for Bogles today. Meet me tonight.

Nine in the morning. School had already commenced. Prayers were over, and my first class was due but did not appear. Carry Poser beamed in upon me directly, with the compliments of Madam Button; and would I go, Miss Bittersweet, and send away a horrid peddler, who was chaffering with the girls in the great hall of the studio? We should all wake up some morning and find ourselves murdered in our beds, that we should!

Peddlers and beggars were stringently against the rules at Button High School. In the great hall I met a small army of Sal Volatiles, with naughty Georgiana Mixer at their head, and Carry Poser, full of logic and curiosity, bringing up the rear. They were clattering about well, but scuttled away at once, making dissolving views of themselves out of side doors to the right and left, as I marched in. There stood Bogles, an old-clothes-man, as Dick had described him. The Camphor Reformation, so named by Miss Mixer, was raging in school at that time.

Professor Th—, music man, was insatiably addicted to meerschaums and general festivity. The Sal Volatiles abhorred stale tobacco, smoke and whiskey fumes. The professor loathed camphor. The girls decided to have it out with the poor gentleman on that base. They regularly mummied themselves in camphor, till they smelted like so many winter furs.

The higher powers interfered. Then it was musk; then kerosene oil. The music-class revelled in kerosene bandoline, kerosene boot- blacking, kerosene toilet perfume. Then it was snuff. You might hear the school sneezing for a half mile, on any clear day.

At length, Jupiter, gathering up his thunderbolts, threatened to expel the offenders from paradise. Whereat they were cut to the heart, and set up a series of weeping-bees, in which they outhowled the howling dervishes, and nearly took the roof off with their woe. Jupiter, pushed to extremity, made signal example of two of the worst-paying Sal Volatiles. The remainder of the society pinned black crape streamers to their door-knobs, and appeared in black paper-muslin mourning, till such time as they were ordered out of it.

Just now it was the reigning whim to carry off the distracted professor’s small possessions, and deposit them, in artistic confusion, about the halls and each other’s rooms. Did “the enraged musician” chance to require such an article as his penknife, his smoking-cap, his walking-stick; alas, he had it to find—if he could.

A miscellaneous heap in the corner of the hall challenged my attention. As Bogles seemed about to pack it in his wallet, I insisted on seeing it explored. Out tumbled Prof. Th—.’s metronome and old gray shooting-jacket, in close fellowship with Miss Grimshawe’s best artificial curls and company turban. The graceless creatures had exchanged them for a cast of the Apollo Belvidere and a Medusa, giving out that their booty was flinging about the studio, belonging to nobody in particular. Well, what could one do about it?

Miss Grimshawe swooped down upon her property, and carried it away in a whirlwind of virtuous temper; I despatched her to conduct the recitation of my troublesome class, not in the least envying the latter.

Bogles, by the way, was exceedingly deaf, and spoke villanous English, elaborately broken. I know a little Italian, but his gibberish was not Italian. Nor was it French, nor Spanish, nor German, nor anything else but a pure invention. He was a goodish-natured looking fellow, not overshrewd in the face, and most doggedly determined to cleave to the professor’s old coat. The other articles as well, never mind! But the cloth things were in his line and he would have them.

What Bogles did with the shooting-jacket was to convey it straight to his den, shut himself in with it, and rip, and pull, and jerk, and tear it to tatters.

Bogles was himself searching for a clue to the diamonds, it appeared.

The case was growing interesting. Dick called in Detective Hansleigh, and placed poor persecuted Prof. Th— under the secret surveillance of police.

Bogles began to haunt Button High School from that day, Dick Masters giving the fellow “plenty of rope,” as he called it.

Bogles came to hang brackets, place busts, statuettes, etc., a department of labor in which he evinced real taste. He dropped in, every now and then, in the way of trade. He supplied our oil-painting woman, a shattered sort of person by the name of Greer, with plaster studies for her class. In the meantime, he made shift to carry on a critical examination of every foot of the school buildings, from the attic down, paint-cave and all.

It seemed most likely that this fellow was one of Dim Dark’s former accomplices, perhaps a relative. That he, like police, was in quest of the diamonds. That he was unacquainted with their actual place of deposits. If otherwise, why did he not secure them at once, every facility having been afforded him for doing so. Apparently, however, he had definite knowledge of a key to their hiding-place, secreted in some article of clothing, not in his possession, which he was making it his business to find, and which he could not find.

Late one afternoon, the fellow passed my class-room window on his way to the studio, carrying a plaster figure in his hand for the modelling department.

Directly afterward Dick Masters emerged from his lair, got up as a day-laborer. He had on a faded stuff cap and fustian pantaloons, and he signified to me, as he walked by, that I was to procure him his gray coat.

At the next interval between classes, I proceeded to obey orders. Locking my door, I got out the garment in question, and prepared to drop it from the window, behind a sort of grape-screen that was growing just underneath.

While I was in the act of folding the coat for this purpose, Bogles reappeared, crossing the green in my direction. The villain chanced to glance upward as he passed. He stopped outright, one foot in the air, as if he had received a blow. He stared, he glared; growing white and red by turns. It did not require two looks to perceive that he had made some important discovery. What was it? It must be Dick’s coat, I reasoned. In fact, it could be nothing else.

“Come, now! it’s this, I’ll be sworn!” said I to myself, by no means aloud. “Equally, I’ll be sworn you [won’t] get it, Bogles! Not while my name is Bittersweet!”

With that, I ran and gave the coat a fling into the depths, not knowing how desperate a game the fellow might be prepared to play.

As I turned about, there was Bogles at the window-ledge, clambering up a grape vine to get in. He doubtless understood from my movements, that he was detected, and felt this to be his last chance.

“You squeak,” says the villain, in English, irreproachable as to accent, “and I’ll put a ball through you.”

But la! what could he do? There was Dick Masters on the war-path not twenty paces behind, seeing whom, he sprang down and ran, Dick giving headlong chase. Pistol-shots were interchanged between the two, but Bogles, doubling among the outbuildings, finally succeeded in eluding pursuit

The whole transaction was so quiet and so rapidly executed, that my logic-class, trooping to the door from an opposite direction, heard nothing of the occurrence. To their extreme satisfaction, I at once despatched them to their room, with an exercise to be written out there.

When the coast was fairly clear, I held up Dick’s coat and shouted below to him, “Eureka! Eureka!”

“Keep cool!” shouted Dick, in reply.

We had recourse to the studio, as that, though a public apartment, could, upon emergency, be perfectly secured against outside intrusion. Dick converted poor little Mrs. Greer, the rightful occupant of the place, into an enemy for life, by turning her out and bolting the door against her. This done, he stepped forth and solemnly shook hands with me. Whereupon he burst into a flow of professional enthusiasm.

“Hester Bittersweet, my girl,” says he, ‘‘you’re a brick.”

We thought it advisable to put up the oaken shutters and light the gas.

Dick trundled an unframed Beatrice Cenci under the light, and turned it face downward upon the floor.

Armed respectively with a jackknife and a pair of pocket-scissors, Dick and I proceeded to separate the parts of the collar, the pocket-flaps, the sleeves, and, finally, the waist. So far, we found nothing; no paper, no trace of the booty.

It is to be observed that we were searching the garment, not for a mere clue, but for the actual diamonds themselves. The single fact that Bogles was in pursuit of this particular article of clothing, unravelled the whole plot of the affair. Tallying perfectly with all the other known facts of the case, it was simply a revelation.

We deposited the fluff from the seams and linings, inside the stretcher upon the canvas of the picture. It was precisely entangled in this fluff, at the bottom of the stuff facing of the short skirt, that we, at length, came upon the diamonds. There were two or three small apertures, pretty well up the front of the lining, where Dim Dark had evidently worked, them in, in her light-fingered fashion.

That was a master-stroke of hers, by the way. Dick speaks of it to the present time, with boundless admiration. Knowing the booty to be unsafe in her own possession, she deftly placed it, while in the paint-cave, on the night of her arrest, upon the person of her jailer, Masters, to whom no suspicion could attach. In the involuntary guardianship of police, the diamonds were quite beyond the pale of discovery; and she might trust luck to secure them, by agent, at a later period. The blue silk of the packet picked up on the studio floor, where she had dropped it, was now an intelligible fact.

They shone out well in the gaslight—the diamonds—I warrant you. First one, and then another. Finally we had gathered up the whole collection, every one of them. It was a truly happy moment, when Mr. Masters counted the last into my open hand.

“Bless us, yes!” says Dick, “here they are, recovered. And who is at the door, now?”

It was only Jupiter, who had, in point of fact, been thumping for admission an indefinite period of time. But we had been too much preoccupied to take notice.

“A most extraordinary proceeding, Miss Bittersweet!” grumbled the thunderer, through a key-hole.

[“]Undoubtedly, professor! Pray come in.”

Dick carefully unclosing the door, admitted Jupiter, barring out the inferior gods.

Still nursing his wrath, Professor Button walked in, and inspected the diamonds spread out upon the palms of my two hands.

“Miss Larkspur’s jewels, kind old friend!” said I. “Mr. Masters undertook, upon his own responsibility, to restore them to her; and here they are, this minute unearthed.”

Questions followed, and explanations without end.

Miss Larkspur showed herself a true woman upon the occasion. I was proud of her. She did not go into hysterics. She shed a few natural tears upon my shoulder, then went up to Professor Button, kissed him, and asked him to wish her joy of her restored fortune.

When Dick Masters, redder than a—a blood beet, if I must say it—blurted out, in his downright fashion, that he liked compliments of that sort passed about, she came, without demur, and kissed him likewise, blushing divinely.

Button High School celebrated the auspicious event by oyster soup and a frosted cake for supper; together with company in the parlors and Chinese lanterns on the lawn, at a later hour.

Nor was that the best of it. By no means.

Dick Masters, the lion of the occasion, being about to leave town that night on the half past eleven train, our guests resolved to remain and conduct him in state to the depot. He was a modest man was Dick, and kept himself out of the throng, mostly.

Not so Lawyer Hare. At the first flurry of news he had come triumphantly, flying on the wings of love and hope, to the aid of his dear. Augusta received the recreant with such undisguised cordiality, that I could have boxed her ears, the minx.

At precisely half-past nine, a delegation of two Sal Volatiles, in their party best, as to costume, presented themselves in the drawing-room, and handed me a note.

“You are to read it, if you like, Miss Bittersweet,” said one of the pair. “Then please pass it to Professor Button.”

I had not my spec—that is to say, I gave the note directly to the professor.

The latter read, knit his brows, smiled, beamed over upon myself and the small committee, and nodded enthusiastically in the affirmative.

A bustle at the door. In came the inevitable Mixer and Poser, as advance guard, followed by Augusta Larkspur and Richard Masters, followed again by the Sal Volatiles, en masse.

Well, the long and short of it is, Augusta and Dick were married then and there. Professor Button performed the ceremony, properly astounding the uninitiated.

After all which, each and every of that remorseless S. V. secret society, Augusta Masters included, marching up, presented to me their united and formal dissolution of the Sal Volatile league and covenant, together with a hearty promise of good behaviour for the future. It was Augusta’s thank-offering. Diamonds would not have been so acceptable to myself and poor Prof. Th—.

I was chatting with Lawyer Hare at the moment, enlarging upon the improved prospects of the newly-married pair, bringing out the sterling points of Dick’s character—embellishing a trifle, perhaps, and so forth. My conversation did not appear to exhilarate Lawyer Hare—not even when—well, in fact, he walked away, put on his hat, slammed the front gate and left me expatiating to the air.

Carry Poser consoled the gentleman. A great many years ago, that is, now. She was ugly and awkward, and worse, she was poor; quite the reverse, in every respect, of what would have been his choice. But she took him logically in hand as her lawful prey, and married him by sheer force of persistence.

And Bogles! We never learned what became of him. Mrs. Masters declined to have him pursued, not wishing further human sacrifice made to the Moloch of her jewelry.

During their bridal trip, by the way, Mr. and Mrs. Masters subjected their diamonds to professional examination. They rated high in the market, Augusta wrote me, having been selected for their purity, by a connoisseur in the article. I am afraid to state their great value now, but it was three or four times what we had all imagined.

The Larkspur diamonds still remain in the Masters family. Indeed, it was only last Christmas, while on a visit to their home, that I saw them blazing from the persons of their beautiful twins, Hester and Georgiana.

* Instructions for using the Key. —1st. Drop all the symbols; their only use is to separate words. —2d. Select the word you wish to decipher; take each figure and letter consecutively and find it in the key. —3d. If the letter or figure is found in the upper line of letters or of figures, substitute for it the letter next below. 4th. If the letter or figure is found in the lower line of letters or figures, substitute for it the letter next above. —5th. A small figure 2 at the right of a letter or of a figure shows that the corresponding letter is to be doubled. Thus in n v2 g the corresponding letter to n is m, to v2 is double e, to g is t—meet.